Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In our original blog, ‘Why Restore Wolves to Colorado,’ we briefly discussed the top five reasons wolves should be reintroduced to the state. Now, we’re digging deeper into each of those arguments. You can also check out Part I: Ecology. Blogs by Gary Skiba, Board Member and wildlife biologist.

Part II: Colorado is the Missing Link for Genetic Resiliency

If you want to look more deeply into some of the effects described here, check out the list of sources at the end.

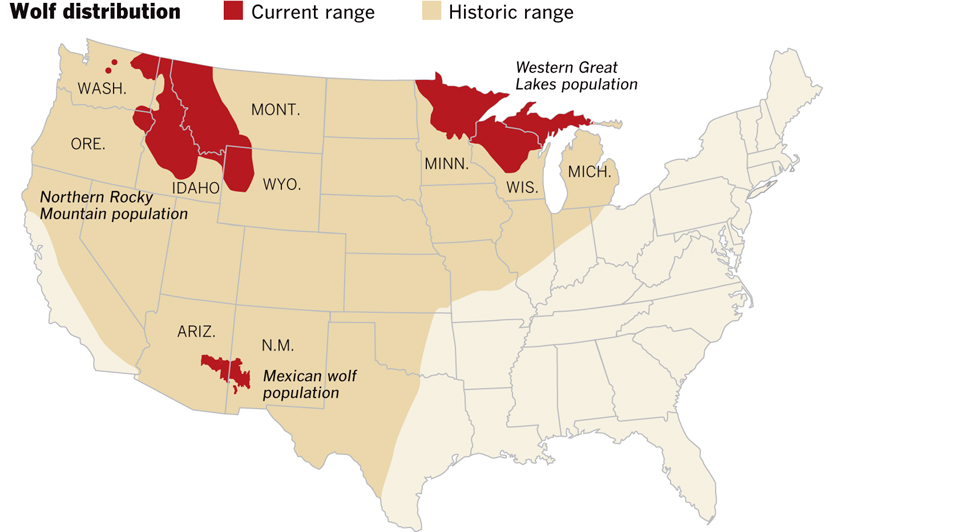

The original range of the gray wolf, Canis lupus, in North America extended from the far northern edge of Alaska to central Mexico and from the west coast to the east, except for the southeastern United States, where it was replaced by the red wolf, Canis rufus. (As a side note, there is still controversy over whether the red wolf is a distinct species, a subspecies of Canis lupus, or possibly a wolf-coyote hybrid).

Many juvenile wolves (similar to other juvenile animals) disperse from the area they were born looking for opportunities to join other groups of wolves or start a new pack with another dispersing wolf. This mixing of animals with different genetic makeup and resulting different physical, behavioral, and physiological characteristics maintains the ability of populations to respond to environmental change, with climate change being one of the most important factors to consider today.

Many juvenile wolves (similar to other juvenile animals) disperse from the area they were born looking for opportunities to join other groups of wolves or start a new pack with another dispersing wolf. This mixing of animals with different genetic makeup and resulting different physical, behavioral, and physiological characteristics maintains the ability of populations to respond to environmental change, with climate change being one of the most important factors to consider today.

Isle Royal

Maintaining genetic diversity is particularly important in small populations. Isle Royale, a National Park in Lake Superior, is instructive in thinking about genetic diversity and wolves. There were no moose on Isle Royale before the early 1900s, when it’s believed a small number of animals swam to the island. The wolf population on Isle Royale started with what is thought to be a single pair and possibly a second male that moved across the ice in the early 1940s and took up residence on the island.

Over the next 50 years or so, wolf and moose populations fluctuated due to the combined effects of a number of environmental factors, including weather, predation (by the wolves on the moose), prey availability (how many moose were available for wolves to eat) and disease. In 1982, the wolf population crashed to a low of 14 animals, due to the introduction of parvovirus through a domestic dog. The population recovered somewhat, but declined again in the 1990s, even though the parvovirus was no longer present and moose were abundant. This lack of recovery is usually attributed to low genetic diversity, also known as inbreeding. In fact, further study of skeletons showed inbreeding-related malformations in the wolves over a long period of time, with one particular condition present in more than 80% of individuals by the late 1990s.

In the winter of 1997, a lone male wolf crossed the ice from Canada to Isle Royale. The introduction of that bit of genetic diversity revived the population, which began to recover…but then the moose population declined, due to unusually hot summers which decreased foraging activity by moose, and also led to a dramatic increase in ticks that fed on moose. The result was weakened moose that underwent a drastic decline, leading to a decrease in available food for the wolves, causing a decline in the wolf population. The multiple factors influencing wolf and moose populations point out the difficulties of predicting exactly what will happen if wolves are restored to Colorado, but the beneficial effects of increased genetic diversity are clear. An excellent description of these interactions, with far more detail, is available here.

Colorado is the missing link

So genetic diversity, which relies on the movement of animals between different populations is important for maintaining resilient and healthy wild populations. The populations of wolves in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and now Washington and Oregon, are exchanging individuals across the landscape. In the Southwest, the Mexican wolf isn’t doing very well, due to a number of factors, with low genetic diversity commonly cited as one issue. All of the Mexican wolves in the wild are the descendants of only 7 individuals, 3 captured in the wild in Mexico and 4 from zoos. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lead agency in the restoration of the Mexican wolf, has tried to carefully manage the genetic structure of the population but with limited beginning genetic resources, it’s a daunting task… which brings us back to Colorado.

If wolves are restored to Colorado and establish healthy populations, young wolves will eventually begin dispersing the state, and wolves from both the north and south will disperse to Colorado. All of these migrants would try to start new packs or make contact with and try to become part of existing wolf packs. This movement of wolves would result in increased genetic diversity, improving the genetic health of any population receiving wolves from another area.

The Mexican Wolf

Some folks have expressed concern about wolves from Colorado moving south and interbreeding with Mexican wolves as that subspecies is listed as Endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act. This is a complex issue that brings together social, biological, and legal issues. The bottom line is that all gray wolves across the world, from Portugal to Mexico to Siberia to Quebec are the same species, Canis lupus. There is disagreement among biologists about how many subspecies of the gray wolf exist across the world or across North America. The reality is that the subspecies of gray wolves display minor variations that are ecologically unimportant. A wolf from Alaska would readily breed with a wild wolf in southern New Mexico, or one from Greenland or Portugal, and would produce fertile offspring, and all of them would affect their environment in identical ways. The addition of more genetic diversity to the Mexican wolf population would enhance the survival of wolves in the American Southwest.

It’s important to remember that before wolves were removed from most of their range in the lower 48 states, they formed one large metapopulation, a conglomeration of smaller populations that regularly exchanged individuals across the landscape. So Mexican wolves, while adapted to the drier conditions of the American Southwest, were regularly receiving individuals from populations to the north and east. Similarly, dispersing Mexican wolves undoubtedly moved in all directions, taking their specific genetic composition to other populations. Over time, Mexican wolves will adapt to their environment and may indeed no longer be a distinguishable subspecies, which is exactly what could have happened under prehistoric conditions.

That’s how wolf populations in North American functioned for hundreds of thousands of years, and restoring wolves to Colorado will be a step towards reestablishing healthy wolf populations across the western United States.

Selected Sources and Background

Adams, J.R., L.M. Vucetich, P.W. Hedrick, R.O. Peterson and J.A. Vucetich. 2011. Genomic sweep and potential genetic rescue during limiting environmental conditions in an isolated wolf population. Proc Biol Sci. 2011 Nov 22;278(1723):3336-44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0261.

Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M. 2012. An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses. North American Fauna 77:1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001

Charlesworth, D; Charlesworth, B (1987-11-01). “Inbreeding Depression and its Evolutionary Consequences”. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18 (1): 237–268. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321. ISSN 0066-4162.

Frankham, Richard (1995). “Conservation Genetics”. Annual Review of Genetics. 29(1995): 305–27. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001513. PMID 8825477.

Frankham, R., Ballou, J., Briscoe, D., & McInnes, K. (2004). A Primer of Conservation Genetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511817359

Lande, R. (1988-09-16). “Genetics and demography in biological conservation”. Science. 241 (4872): 1455–1460. doi:10.1126/science.3420403. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 3420403.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/2535

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, First Revision. Region 2, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/mexicanwolf/pdf/2017MexicanWolfRecoveryPlanRevision1Final.pdf

Vucetich, J. A. and R.O. Peterson. 2004. The influence of prey consumption and demographic stochasticity on population growth rate of Isle Royale wolves Canis lupus. Oikos 107:309-320.

Vucetich, JA and Peterson RO. 2012. The population biology of Isle Royale wolves and moose: an overview. URL: www.isleroyalewolf.org

Willi, Yvonne; van Buskirk, Josh; Hoffmann, Ary A. (2006-01-01). “Limits to the Adaptive Potential of Small Populations”. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 37: 433–458. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110145. JSTOR 30033839.

The 1982 IRNP Parvo event is relevant to the discussion of C l baileyi and its future.

All subspecies develop through adaptation – phenotypes are selected for or against. the immense breeding effort for baileyi is essential, as the artificial bottleneck induced by gun hunting, poisoning, and trapping was one incidence of nonadaptive artificial selection, possibly inducing greater vulnerability to inbreeding depression, etc.

Isle Royale borders most closely the NE Minnesota and Thunder Bay area – which has been massively built up since the time I was a child first hearing wolves. What this, along with increased mean temperatures resulting from anthropogenic global heating, implies, is that wolves, if and when persecuted further, would less often have iced-over Lake Superior to cross.

What this meant was that 1982-4 constituted a bottleneck event which may have sped the inbreeding spinal problem and the reproductive depression , quickening the doom of the self-dispersed IR population.

Like other species, wolves appear to avoid inbreeding as much as possible. This is ancient, molecular, related to arousal in ways too complex to discuss here. But just as interesting anecdote and some info to lead readers further into understanding the wolf please indulge: I’m familiar enough with wolves to have both observed and experimented with their molecular sense, which remains astonishing.

I’ve witnessed a wolf ambling along waterside with waves lapping sufficiently to periodically cover the beach zone. He suddenly became as if electrified, taking off north, where, when I followed, he encountered his conspecifics a couple miles up. This was on a strand where all footprints had been washed away. On another occasion following a young wolf I recognized 5 days earlier at a carrion site, I saw and tracked it about 4 miles through dense riparian forest THAT I KNEW THAT INDIVIDUAL HAD NEVER PREVIOUSLY PASSED to reach the 5-day old site. He had arrowed directly to the upland meal. In the latter case, the wind had not been in his face, and I had to tentatively attribute the event to some memory/associative brain mapping.

Cognitive science is working on such mysteries as spatial orientation, which may or may not significantly involve indirect smell iron-containing neural nuclei, and other stuff.

Because brains are “prediction organs” more sophisticated than the simple molecular detection occurring on cellular surface and intracellularly in non-neuron-possessing organisms, as well as being largely involved with evaluation of probabilities (albeit heuristically!) and long-sharpemned by evolution for maintenance of the possessor’s life through seeking efficiency (“laziness” comes to mind, as minds eat a lot), it also comes to aroused mind that the few wolves entering Colorado since reintro in Y’stone, had suffered from the specious designation of a “Northern Rockies Distinct Population Segment”, and consequent Euroamerican resurgence of persecutory “management” in Wyoming.

Here, I just want to suggest that long distance dispersal may not be at all as random as the worn-out past null hypotheses of randomness. After all, Minnesota wolves are recorded, unfortunately through their deaths (by both gunfire and highway fatalities), as far as Missouri, and Illinois/Indiana.

Far west beyond the Rockies, checking dispersal patterns led to observing differences in Interstate Highway traffic – night being most important – between I-84 in eastern OR and I-5(the biggest and recovering Cervus species are still unkown to present wolf generatins, from Olympics to OR and CA coastal wildlands (or chainsawed lands, as you prefer), I strongly suspect that I-5 constitutes a shocking barrier, with its never-ending heavy traffic.

Oregon wolves have not dispersed across that barrier in the many years now they’ve had access, instead keeping to the Cascades. This issue has consistently been ignored by managers, due to all the previous extirpation and DPS scat-of-another-aroma.

Chasing a bit of normal wolf scat over some divides, I note that I-15 is not a problem, but the failure of ESA through 1994’s compromise 10j rule and the DPS criteria separating Colorado from the 3 persecutory states to its north have introduced some complexity.

Idaho’s ecologically and legally released human persecution has slowed genetic flow west as well) I don’t believe that CO’s I-70 would be so much a barrier, but NM/AZ I-40 is, for two reasons. Presently baileyi is banned from crossing I-40 as a 10j nonessential. Unless and until such rulings are reversed, draconian constraints on natural gene flow would continue. Nature, in short (or female wolves – secure wolf bonding appears to be mutual choice,but skewed toward the female. Those unfamiliar should see sexual selection for insight. The famous common word is especially appropriate for females’ rightful choices. . . ), will not be allowed its effective adaptive selection.

Hopefully CPW will attend more to the needs of North America’s native, persecuted, endangered species, than to the testy, greedy gun-totin’ omnivore so excessively and aggressively sure of its “ownership” of all that is.