Background

Bighorn sheep are an iconic species of the American West. They call some of our country’s most rugged and remote landscapes home. Their cultural, ecological, aesthetic and economic value has made bighorn sheep a vital part of North American heritage.

Bighorn sheep are extremely sensitive to changes in the environment and are considered an indicator species. Indicator species can signal changes in the biological health of an ecosystem. Bighorn sheep exist in metapopulation structures, which means they move between mountain ranges to reproduce with other sheep populations in order to maintain genetic diversity. Thriving metapopulations occur on interconnected landscapes, with corridors and contiguous swaths of habitat. So, a healthy, flourishing herd is indicative of a robust and flourishing ecosystem.

Bighorn sheep were once among the most abundant wild ungulates in the American West, with populations ranging from 1.5 to 2 million at the turn of the 19th century. Historically, their population ranged from Canada to northern Mexico, and from the Pacific coast to the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Texas. With westward human settlement, bighorn sheep populations declined precipitously, due in part to unregulated hunting, disease, and overgrazing of rangelands. These declines have continued over time and existing populations throughout the west remain at risk.

Disease and Bighorn Sheep

Disease transmitted by domestic sheep (that graze on public and private lands throughout the western United States), remains one of the most critical threats to many bighorn sheep populations. Domestic sheep are healthy carriers of bacteria that causes fatal pneumonia in bighorn sheep. When the species come into contact or are in close proximity, disease can spread and decimate wild populations. Pneumonia outbreaks frequently cause major die-offs, reducing populations by 50% or more. Even if some bighorn sheep survive, it can take years for the herd to recover and recovery is not guaranteed. There is currently no way to treat bighorn sheep for pneumonia, so separation of bighorn and domestic sheep is the most effective management tool available.

San Juan Mountains Bighorn Sheep Populations

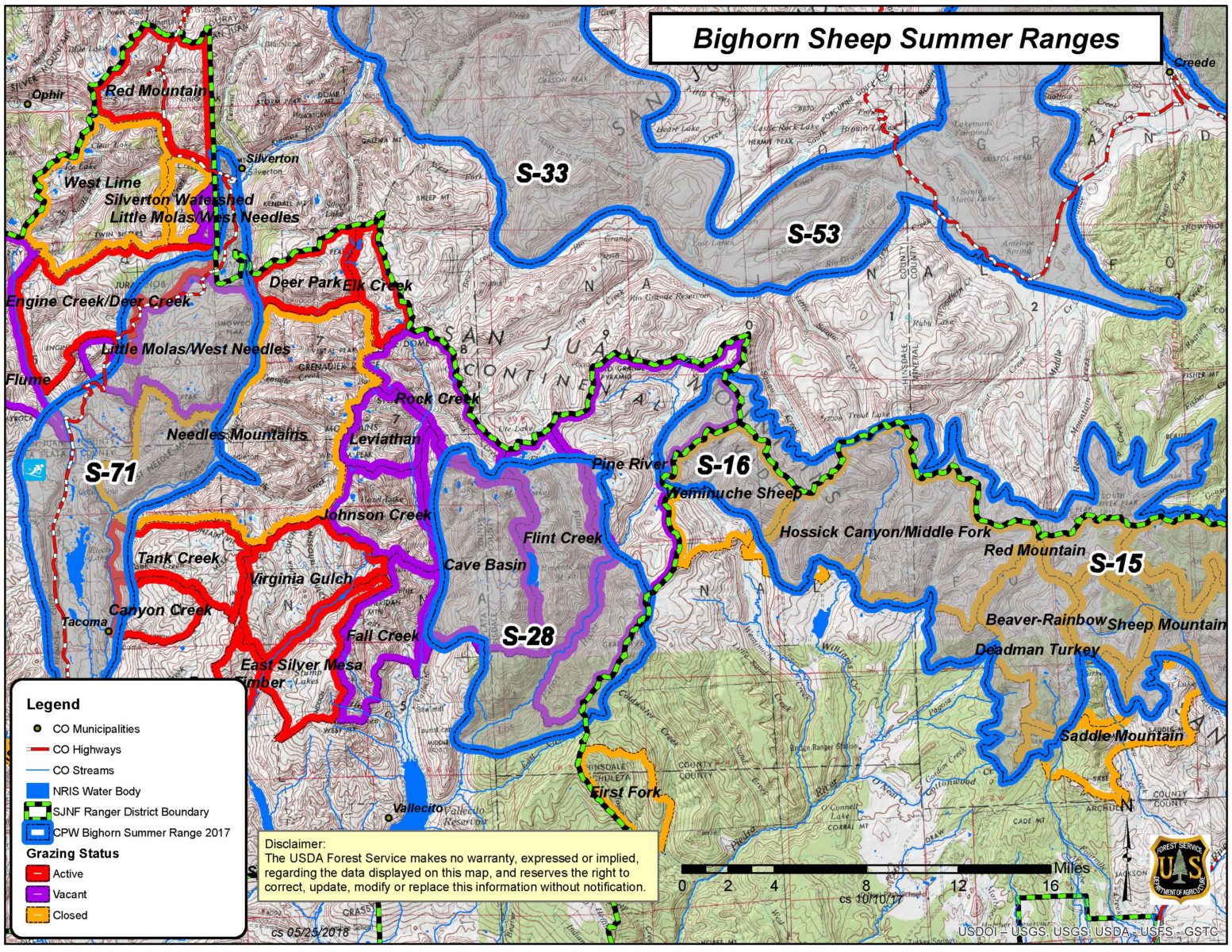

Locally, the San Juan Forest is home to five herds of bighorn sheep, the West Needles Herd, Vallecito Creek Herd, Cimaronna Herd, and Sheep Mountain Herd and the South San Juan Herd. The Vallecito Creek, Cimarrona and Sheep Mountain herds combine to form “RBS 20” a metapopulation of approximately 450 individuals, which is considered a “Tier 1” population by Colorado Parks and Wildlife – this means they are native to the area and have not been transplanted from other populations. Weminuche bighorns are listed by the Forest Service as a “sensitive species,” meaning there is concern for their long-term survival.

Of particular concern are active domestic sheep grazing allotments in the Weminuche Wilderness between the Animas River and Vallecito Creek, south of Needle Creek and Chicago Basin. Ensuring that domestic sheep on these allotments do not come into contact with wild sheep is key to the survival of bighorns.

What can you do right now to protect bighorn sheep?

What can you do right now to protect bighorn sheep?

Protecting bighorn sheep in the San Juan Basin requires a collaborative approach focused on scientific integrity and transparency. You can play a part in protecting bighorn sheep right now!

Mountain Studies Institute has developed a citizen science monitoring program for bighorn sheep to help alert local land managers when bighorn sheep and domestic sheep may potentially come into contact. When you go hiking in the alpine, you can take photos of bighorn and domestic sheep and pack goats. Using a simple app, you can report your observations and submit photos straight from your smart phone. This tool provides critical data for scientists and land managers to understand the risks of contact between the species. For more information visit: http://www.mountainstudies.org/bighorn

To protect bighorn sheep is to protect the San Juan Basin ecosystem that we all call home!