In our previous blog, ‘Why Restore Wolves to Colorado,’ we briefly discussed the top five reasons wolves should be reintroduced to the state. In this and future blogs, we’re digging deeper into each of those arguments. Blogs by Gary Skiba, Board Member and wildlife biologist.

Part I: Wolves perform important ecological functions

If you want to look more deeply into some of the effects described here, check out the list of sources at the end.

As with all things related to wolves and field biology in general, the ecological functions and effects of wolves are complex and not always clear. There is no question, however, that wolves cause profound change in the behavior of their prey, creating other effects in the environment; wolf predation also improves prey population health. Together, these changes are referred to as a trophic cascade, where changes at one level of ecological organization cause changes in other levels.

One of the most important concepts to keep in mind is that wolves, their prey, and the ecosystems they interact in functioned and evolved together over hundreds of thousands of years. The gray wolf, Canis lupus, evolved approximately 300,000 years ago. Since then, many large animals (ground sloth, wooly mammoth, horses, camels) have disappeared, but the wolf has continued to survive and thrive, except when faced with determined human efforts to eradicate them. Wolves now specialize in hunting ungulates, including elk (especially elk), deer, caribou, moose and bison, and the ongoing influences of predator on prey and prey on predator continue.

Effects on prey behavior

Hunting by wolves causes changes in prey behavior, which can create environmental change. In Yellowstone National Park, changes since wolf reintroduction in 1995 include improved conditions in riparian areas and higher survival of aspens and willows. Most researchers attribute these changes to shifts in elk behavior. Elk that stay on alert to the presence of wolves are less likely to remain in riparian areas for long periods, resulting in less intensive browsing. Both beaver and bison populations increased over those years; beaver activity is helping to restore degraded riparian areas, which support a wide array of wildlife species, from small mammals to birds.

Can we directly attribute these effects to the presence of wolves, and will the same effects occur if wolves are restored to Colorado? The answers are a bit murky, but based both on the experiences in Yellowstone and ecological theory, they are a qualified “yes” for both questions. As noted above, ecological interactions and effects are complex, with many variables. Weather, hunting pressure, other predators, and human activities all influence elk numbers and behavior. We know for certain that elk will respond behaviorally to wolf presence, and that change in behavior will almost certainly cause positive change in environmental conditions.

Prey Selection

Wolves prey on the most vulnerable individuals; in the case of elk, those are the young (calves) and older females. Wolves are coursing predators, meaning that they approach their prey and then pursue fleeing individuals. They quickly determine if any individual animals are impaired in any way and they focus on them. Impaired animals are not only easier to catch, they also are less dangerous. Many wolves end up injured during hunts, mostly by the sharp hooves of the animals they prefer.

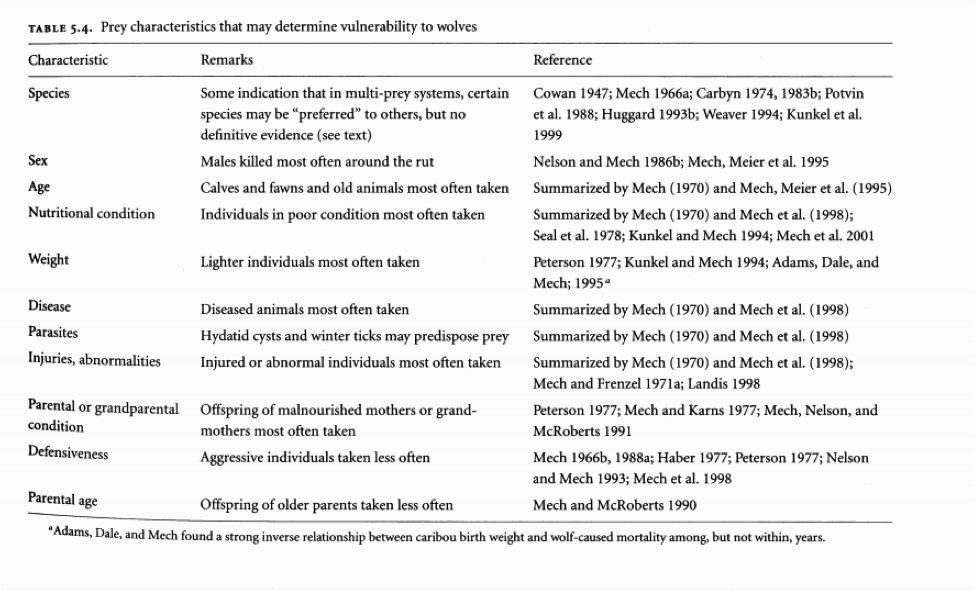

The table below from Mech and Peterson (2003) summarizes some of the scientific evidence of the many factors that can make prey more vulnerable to wolf predation.

In a Yellowstone area study, the mean age of adult females killed by hunters was 6.5 years, whereas the mean age of adult females killed by wolves was 13.9 years. Wolf killed elk cows are more commonly at the end of their reproductive years, while hunter killed elk commonly had multiple years of reproduction ahead of them. Removal of more animals in their prime reproductive years makes the population less resilient and less able to respond to factors (like a harsh winter) that reduce population size. Removal of weaker individuals results in healthier prey populations

Effects on Vegetation

Ripple and Beschta 2011 reviewed multiple vegetation studies that demonstrated the changes that occurred in Yellowstone National Park after wolves were reintroduced. These changes were likely caused more by changes in prey behavior and not by reductions in prey populations. The prevailing belief is that prey animals (particularly elk) are more alert and spend less time in any one location when wolves are in the vicinity. Riparian areas, those thin bands of vegetation along streams and lakes, are one of the vegetation types showing significant change. Some researchers attribute those changes to the fact that elk don’t spend as much time in those areas, allowing willows and cottonwoods to survive and grow due to less browsing by elk. There are other researchers who think the explanation is more complex and that beavers are a key factor in the re-establishment of healthy riparian vegetation. It’s a bit of chicken and egg situation, as beaver dams create better conditions for establishment of riparian plants, and beavers need riparian plants for food. What is clear is that conditions have improved for beavers, songbirds, and small mammals. The habitat is better for elk as well, because the food plants are both more abundant and more nutritious.

Scavengers

Mark Hebblewhite and Doug Smith (2010) listed species they observed on 221 ungulate prey carcasses between 1995 and 2000 that were killed by wolves. In Banff National Park, they tallied 20 species: Most common were ravens (present at 96% of all kills), coyote (51%), black-billed magpie (19%), pine marten (14%), wolverine (8%), and bald eagles (8%); others, in descending order, were gray jay, golden eagle, long- and short-tailed weasel and least weasel, mink, lynx, cougar, grizzly bear, boreal and mountain chickadee, Clarkʼs nutcracker, masked shrew, and great grey owl. In Yellowstone, they noted twelve scavengers, of which five visit virtually every kill: coyotes, ravens, magpies, and golden and bald eagles.

More species of beetles use carcasses than all vertebrates put together. Sikes (1994) found 23,365 beetles of 445 species in two field seasons at wolf-killed carcasses. No predator feeds as many other creatures as wolves do.

SELECTED SOURCES

SELECTED SOURCES

Alston et al. 2019. Reciprocity in restoration ecology: when might large carnivore reintroduction restore ecosystems? Biological Conservation 234:82-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.021Get rights and content

Cusak et al. 2019. Weak spatiotemporal response of prey to predation risk in a freely interacting system. J. Animal Ecology 2019: 1-19

Marshall KN et al. 2013 Stream hydrology limits recovery of riparian ecosystems after wolf reintroduction. Proc R Soc B 280: 20122977. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2977

Mech, L.D. and R.O. Peterson. 2003. “Wolf-Prey Relations” USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 321. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/321

Mech, L. D., and L. Boitani (eds.). 2003. WOLVES: BEHAVIOR, ECOLOGY, AND CONSERVATION. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, and London, United Kingdom. 448 pp.

Ripple, W.J., Beschta, R.L. 2011.Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: The first 15 years after wolf reintroduction. Biol. Conserv. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.005