Nearly four decades ago, Billy Joe “Red” McCombs – the Texan billionaire who built an empire spanning car dealerships, media, and sports – teamed up with Mineral County landowner Charles Leavell to form a real estate venture. Red owned three parcels of sagebrush in the San Luis Valley (SLV) near Saguache, but his sights were set on Wolf Creek Pass.

Wolf Creek Pass straddles the Continental Divide between the SLV and the San Juan Basin, spanning the unprotected saddle between the Weminuche Wilderness and South San Juan Wilderness. Highway 160 crests the pass at 10,857 feet, with steep grades on either side that scared CW McCall enough to pen a country song about it in 1975.

The remote terrain provides critical habitat for threatened lynx, calving grounds for elk, and is a favored spot for wolverine reintroduction. The pass has some of the highest annual snowfalls in Colorado, supporting a laid-back ski hill and excellent backcountry recreation. When the snowpack melts, it yields water resources for communities downstream, including irrigators on the notoriously overtapped Rio Grande River. The Rio Grande National Forest is responsible for managing all of these resources on behalf of the public.

In 1986, the newly incorporated Leavell-McCombs Joint Venture (LMJV) swapped Red’s lots in the valley for a private, 300-acre parcel atop Wolf Creek Pass in a controversial land exchange with the Forest Service. The parcel is an “inholding,” a private island in a sea of public land, isolated from Highway 160 by a strip of National Forest. It’s politically situated in Mineral County, one of the least populous counties in the state, with fewer than a thousand residents. The lot is perched on 52 acres of wetlands including 25 acres of fens (rare alpine wetlands that take thousands of years to develop), eight springs, and thousands of linear feet of streams.

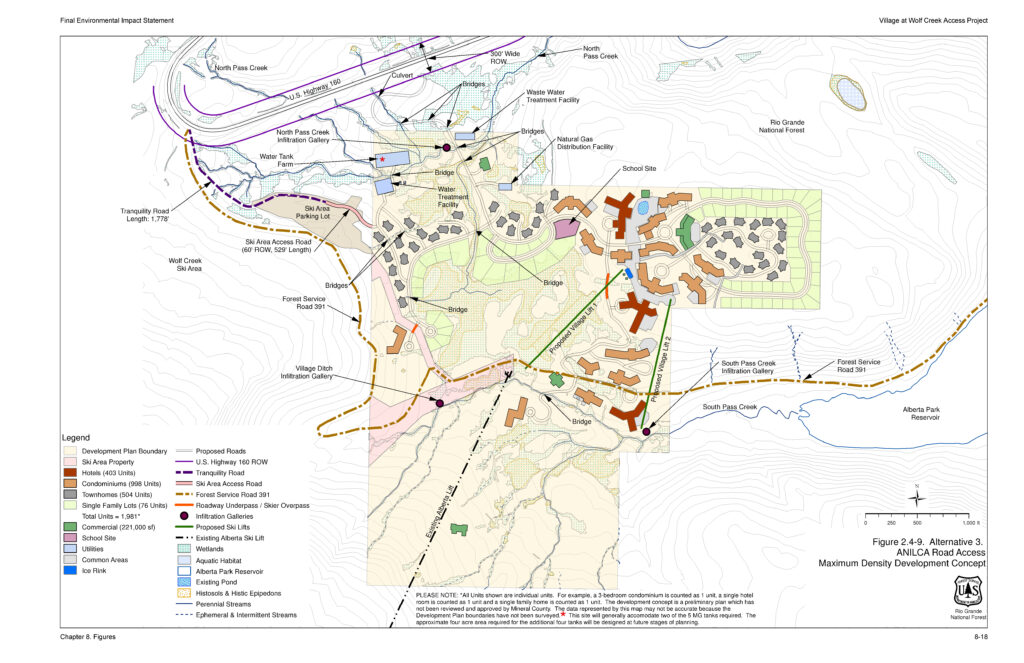

LMJV initially proposed a 200-unit “village” on the parcel to serve visitors to the adjacent Wolf Creek Ski Area, a separate, family-owned hill that operates on permitted public land. But everything’s bigger in Texas, and Red’s dream soon expanded into an 8,000-person luxury resort – with 3 hotels, 15 condos, 42 townhomes, 76 single-family lots, and a school, all supported by a water storage and treatment facility, a wastewater treatment plant, and a private, onsite gas-fired power plant. To top it off, 221,000 square feet of commercial space would ensure guests eat at Red’s restaurants and shop at Red’s retail establishments.

The Village at Wolf Creek was to be a shining metropolis to rival Aspen, five times the population of the nearest town, Pagosa Springs – 24 miles and 3,000 feet down valley – and twenty times that of South Fork, the nearest town north of the Continental Divide.

The Village, perhaps better known as the “Pillage” at Wolf Creek, spurred years of environmental litigation. Conservationists including San Juan Citizens Alliance beat back various development schemes in court, prevailing in state court in 2007, and federal courts in 2017 and 2022. Judges repeatedly ruled that the Forest Service, the agency responsible for approving access to the inholding, failed to adequately consider the environmental impacts of development.

Thirty-seven years after its initial proposal, both Leavell and McCombs have passed away, but the Pillage at Wolf Creek lives on. Like a hungry zombie, it returns again as its appetite grows. In April 2024, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Forest Service must issue a right of way to LMJV, now a faceless legal entity, to access its inholding for the purpose of developing a resort. For the first time since 1986, a court paved the way for the Pillage’s construction. Environmental groups may petition for a rehearing, but for the time being, the decision stands.

As of now, the “Village” is merely conceptual. The Court has ordered the Forest Service to approve a right of way, but numerous state and federal permitting agencies must approve aspects of the development and its connection to Highway 160.

Studies indicate that the Village would increase traffic by thousands of vehicles each day. What’s more, the proponents lack an adequate electric supply. They are proposing to build their own two-megawatt natural gas-fired power plant, provisioned by tanker trucks filled with liquified natural gas. The Colorado Department of Transportation must ensure public safety on the highway, which could require building a major new interchange at the developer’s expense.

The Village’s exceedingly junior water rights on creeks feeding the Rio Grande are likely insufficient for their expanded plans. Irrigators on the Rio Grande and its tributaries are routinely cut off by “calls” from senior water rights holders, and this scarcity will worsen with climate change. The Forest Service admits the project will harm water quality.

Much of the property is covered in wetlands. In the wake of the US Supreme Court’s recent decision in Sackett, it is unclear whether the US Army Corps of Engineers would have jurisdiction over them. The State of Colorado recently passed legislation to protect wetlands no longer under federal jurisdiction. Even if the developers don’t need permits from the Army Corps, they will likely need permits from Colorado.

There are no emergency services available locally. Emergency care on the pass is currently provided by the Archuleta County Sheriff’s Office out of Pagosa Springs. Medical services are scarce. Mineral County and neighboring Hinsdale and Archuleta counties have all been flagged as Health Professional Shortage Areas by the U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. The only healthcare provider in Mineral County is a family practice in Creede, 40 miles from the pass. The Village would increase the county’s population tenfold, further burdening these already strained services.

The Pillage at Wolf Creek is an ill-conceived fantasy of an out-of-state billionaire, who railroaded his vision through the federal bureaucracy without regard for the environment and communities it impacts. To build an entire city from scratch – water treatment plant, sewage treatment plant, on-site power plant, utilities, roads and a highway interchange – will easily run into the tens of millions of dollars. And if it’s constructed, it will be local residents who shoulder the harm – degraded wildlife habitat, water, and air quality. More traffic and risk on our roads and pressure on public services. And, less tangible but nonetheless important, the loss of character as a locally cherished ski area and backcountry playground becomes engulfed in yet another “luxury” resort.

San Juan Citizens Alliance is rolling up our sleeves once again to stop the Pillage.

We need your help. Please consider: