Big Picture

As we breathe a collective sigh of relief after the prolonged and mostly gentle rains that calmed the fire and cleansed the air over June 16-17, we can begin to assess the 416 wildfire from a couple steps back from the fire line. We need to acknowledge, however, that the 416 is yet to be contained, meaning structures and the well being of firefighters are still at risk until full containment. We must also express our deep gratitude to the hundreds of firefighters and other specialists who, through skill, patience and determination, have amazingly managed to contain the 416 to prevent loss of life and structures – thank you!!

First, the 30,000-foot view. Yes, fire is absolutely an elemental part of forest ecology and, for the most part, the forest is going to regenerate and do its thing without any help from us. Our role is to continue protecting people and structures from flooding, debris flows and the risk of future fires in the wildand-urban interface (WUI).

Living and working in Colorado forests comes with a certain amount of risk. Proactive and science-based management of forests in the WUI and creating defensible space around homes and businesses is therefore a responsibility we must take seriously. Remember, the forest was here first. We moved into its home, not the other way around. In the hotter and drier conditions we’ve exacerbated with climate change, the risks have increased.

While we know some basic information about the fire, mostly there are scores of questions to be pursued in order to address both the short term challenges, such as flooding, water quality concerns and burned-area hazards, as well as the long term ones, such as the efficacy of fuel treatments in the WUI and prescribed fires somewhat deeper in the woods.

This first blog will address some basic forest and fire ecology we think helpful to understand as we gather more information about the 416 fire. We’ll address other issues in future blogs. If there are specific topics you are interested in, please post a comment below.

Fire Severity

We do know that within the 50+ square miles of the 416 fire perimeter there is significant forest acreage that was unburned, a percentage yet to be determined. Essentially, most wildfire burns resemble a mosaic, as fire is influenced by numerous variables, such as topography, aspect, soils, vegetation/forest type, burn history, fuels condition, weather during the fire and so on. All of these factors that together create the post-burn mosaic also influence the fire (or burn) severity within the fire perimeter. The headline photograph above as well as the picture below show what this mosaic looks like. They were taken from County Road 201 in Hermosa near the forest closure and demonstrate the patchiness of burned areas as well as the variety in burn severity. For a more expansive view, you can check out our 15 second video here.

Fire severity, generally mapped as low, medium or high, will be found to vary greatly across the 416 fire perimeter. Initial peeks into the burn indicate that high severity areas do exist and some are located on slopes where the fire ran hot and uphill – a behavior at which wildfires excel. And certainly there are locales where the fire was less severe, burning relatively cooler due to such factors as reduced fuel loads, benign weather, and/or downhill slopes. It will take a few weeks before the Forest Service and its partners can map and share a fire severity map with the community, but it will be a critical informational tool for us to better understand the “burn mosaic” including which areas were burned to what degree of severity.

The fire severity mapping will enable us to anticipate (though certainly not to predict) such possibilities as flooding, prospects for debris flows, the timeframe to reach some level of stasis per erosion events, vegetation regeneration response, and more. Frankly we are hoping that the fire severity mapping will reveal a relatively low percentage of high severity acreage (such as 10%) rather than a high number because the watersheds impacted by 416 are interwoven into the economic and social web of our community. Remember that wildfire is a natural phenomenon and is ecologically beneficial to the forest, but like some other natural and human behaviors “too much intensity is sometimes a problem” – especially if the fire burned more in the “frontcountry” than “backcountry.” In sum, we are awaiting the formal Forest Service assessment of fire severity to boost our understanding of the fire event and its “progeny.” We’ll report on that once it comes out and we have a chance to review it.

Forest Types & Past Disturbance

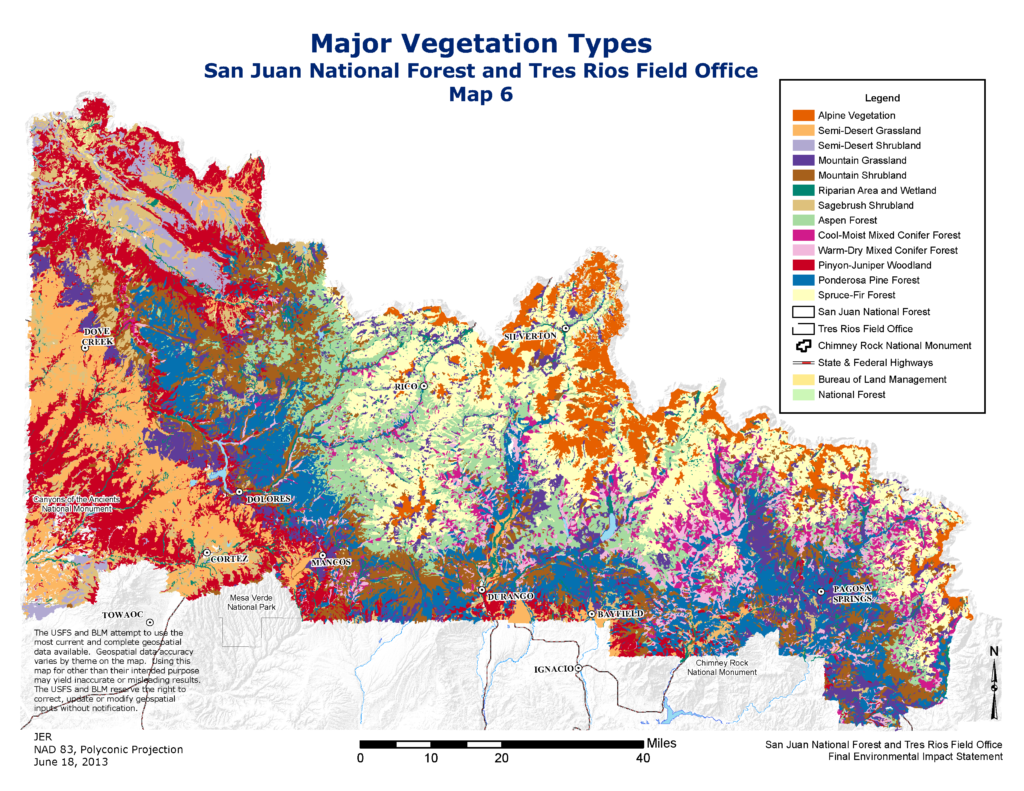

As noted above, a couple important components of the fire severity puzzle are the vegetation/forest types that fueled the fire and the localized history of forest disturbance, whether it be fire, disease, wind events or insect infestation. While we don’t yet know the fire severity, we do know which forest/vegetation types were within the 416 perimeter as both federal and state agencies have mapped such in a detailed manner (see below). That, combined with knowledge of past disturbance events, allows us to make some general assumptions at this point regarding possible burn severity.We must remember, however, that aspect, slope, weather, and so on all contribute to the fire severity reality.

The vegetation/forest classifications within the 416 burn area are mountain shrubland, ponderosa pine, warm-dry mixed conifer (usually growing on warmer/dryer aspects than its brethren cool-moist mixed-conifer), cool-moist mixed conifer, aspen and spruce/fir. The 416 will have traversed the entire scope of major veg types except for the PJ (pinyon-juniper) down low and the alpine tundra up high. Certainly riparian and wetland areas also burned, and aspen stands that we knew were vulnerable in these wickedly dry conditions, also .

Ponderosa

Some of our forests, notably the ponderosa-dominated sector, is a fire-adapted forest. Ponderosa forests in our corner of Colorado benefit from the wildfires they have co-evolved with over the millennia. In general, prior to humankind’s vigorous fire suppression realm over the last century or so, ponderosa pine forests burned at roughly 5 to 20 year intervals. These fires, which were more often–than-not of low severity, reset the ponderosa forest for resistance from fires with long-flame length (old ponderosas lowest-to-the-ground branches are dozens of feet above ground), set-up perfect conditions for regeneration, opened forest canopies and created meadows, and otherwise promoted a “ponderosa first” situation. If you have hiked into the Hermosa Creek watershed from the southern trailhead you have walked through these magnificent stands of rotund and towering ponderosas.

Spruce/Fir

While the ponderosa forest evolved in a tight relationship with wildfires, other forest types evolved with a very different relationship to disturbance events such as fire and insect outbreaks. The spruce/fir forest is one of those. In general terms, disturbance cycles within the spruce/fir forest are not common, but when they do occur, they can “go big.” As such, we are likely to see some of this within the 416 perimeter where some of the spruce/fir forest will have burned extensively and with high severity. The spruce/fir forest has historically not been particularly vulnerable to fire events with their fire interval being counted in centuries rather than years due to its general characteristics of being high, cool and moist. However, with the drying and warming climate (from a long term perspective) and with the exceptional drought conditions (of the short term perspective) we know that the 416 fully engaged the spruce/fir element of the forest.

Resiliency

Optimally our federal, state and private land forest stewards manage forests to enhance their resilience. Resilience is a complex topic within forest ecology and we will explore it further in future SJCA forest and fire blogs. At this point in time we need to be patient and wait for more in-depth post-fire assessments to better understand the dynamics of the 416 and it’s nearby western sister the Burro wildfire. Meanwhile our community should concentrate on our own resilience as we deal with displacements, economic hardship and coming to grips with a changed forest landscape. With it’s proximity to homes, businesses and infrastructure the 416 fire spawns many questions that our community should engage, including those related to land use planning, building codes, travel restrictions, WUI development, infrastructure design and more. It will be a stiff challenge to measure up to the inherent resiliency of our neighboring forests, but we know we can pull together as a community to design and create an enhanced resilient future for both our human and natural communities.

Jimbo, ponderosa pine forests and dry mixed-conifer forests (ponderosa pine with other trees) around the West and here in Colorado are now recognized to have been shaped by mixed-severity historical fires, not necessarily mostly low-severity. Our 2018 scientific paper in Ecological Applications shows, using landscape-scale evidence, that the Colorado area to the north of the San Juans historically had dominantly high-severity fire in ponderosa and dry mixed-conifer forests, but with a mixture of other fire severities. We do not yet have similar published landscape-scale evidence about historical fire severity in ponderosa pine and dry mixed-conifer forests across the San Juans, although I have a paper in review on this topic. But, based on nearby ranges, it is likely that there was a variety of fire severities within ponderosa and dry mixed conifer, possibly with quite a bit of moderate- and high-severity fire. Also, the 5-20 year intervals you mention are not the estimated historical intervals between fires at a point in these landscapes, but instead based on older, rough counts of fires within some distance of points, a subtle but important difference. The true mean historical interval between fires was likely longer, based on new methods that more accurately estimate this statistic. Most important, the San Juans and some other mountain ranges historically mostly had abundant understories of Gambel oak and other shrubs (grassy understories in some places) that promote moderate- to high-severity fires by naturally providing ladder fuels that bring fire up into the canopy. I hope I will be able to release new landscape-scale historical evidence soon about these forests and how they were historically. In the interim, it is best to be cautious about how much is understood about these forests historically, as it is likely incomplete at best. For example, as you know, a 25,000 acre moderate- to high-severity fire, in the same ballpark as our 416 fire, occurred in 1900 in ponderosa and dry mixed-conifer forests north of Pagosa Springs and was reported then in the local paper, but has been generally forgotten in the region. Dr. William L. Baker, Emeritus Professor, University of Wyoming, now a Durango resident.

Thanks Bill for providing all of us with some updates discovered through your research and we look forward to you sharing your coming research findings. In general, I hope all readers can appreciate the challenges of attempting to reconstruct such aspects of our southwest Colorado forests such as forest structure, vegetation types, fire interval and so forth going back centuries or millennia. As no one seemed to be taking detailed notes over the past 500 years (!), the reconstruction needs to be attempted through all types of historical records (including photos, written descriptions and land surveys) along with in-the-forest evidence such as fire scars and tree ring dating (dendrochronology). Fortunately, as our forests are rapidly changing in this era with a continual set of disturbance events, there are numerous institutions and individuals probing these changing forests and attempting to contrast and compare the historical range of variation within forests with what we observe today, while also conjecturing the structure our future forests.

Hey Dr. Baker,

I did not realize you were now a Durango resident. I would love to chat more with you in regards to the fire you are recalling from 1900 north of Pagosa Springs. I appreciate you bringing your research to this discussion. I think the Covington et al. and Fule perspective of Fire in SW Ponderosa Pine forests is often conveyed in an over simplified manner, leaving out potential for spatial and temporal variation in fire severity. Indeed, many of the publication they push out on this topic are done in areas with limited topographic complexity and in more homogenous forest structures (or historical forest structures). I think the spatial complexity in geographies like the Hermosa Creek watershed should naturally create a more complex burn mosaic with moderate to high severity fire occurring on steep slopes driven by wind and topography, such as your publications suggest. I think the two models likely coexist given geographic complexity and the points made by Jimbo stand true in certain contexts, just as the asserations made by your research stand true in alternative contexts.

Thanks for sharing Jimbo and Dr. Baker. A great conversation.

Thank you for the great information! I was recently asked by my 10yo if (once the fire was completely contained) we could go up to the burned areas to begin replanting trees. I wondered if you had any information as to how, when and what resources are available to begin to replace theses trees. Thank you as always for your efforts to educate and propagate information.

James and son – thanks for your interest in our local forests. The good news is that generally our forests are successful at replanting on their own, most likely due to their regenerative practices honed over tens of thousands of years. It is important to understand that the next (and continued) forest we see locally will in some ways look and act differently than the forest we knew on May 31 that are now within the fire perimeter . While some forest/vegetation types will regenerate their own kind (ponderosa generally do this) there will also be areas where the forest type will change. We will explore this in a future blog, but do remember that many aspects of the natural world are secessional in the long term, certainly forests are. With that in mind, we will likely see an increase in pioneer species such as aspen in the evolving forest just as we have seen across the Animas Valley from the 416 fire where the Missionary Ridge fire burned in 2002. For those eager to pitch in with their hoedads (the classic tree planting tool) we’ll need to be patient and see if the San Juan National Forest land managers discover locales where some tree planting might be a wise choice. Within the 72,000 acre Missionary Ridge fire some tree planting has taken place, but in the overall scale of forest it’s a very small percentage.

This. Is. Awesome. You guys do such an excellent job at everything you tackle. Proud to support your work! The depth of this article is very educational for those of us new to the area. My east-coast forests were SO different!

Thanks Karen. Eastern forests or western forests – all are full of complexities and much is rapidly evolving during this significant change in our climate, The challenges to understand dynamics within the forests and how to manage them for the unknown climate ahead are immense – certainly an informed and involved community can help our land managers make smart decisions as we look ahead – please stay tuned and involved!

Thank you! I have a difficult time not holding my Sen. Gardner and Rep. Tipton for voting for everything that add to drought, flooding and billions of dollars of damage, and mostly loss of our forests–they need to burn but past suppression of fires have led to these infernos. When people build in the forest they know the risks. I don’t think tax dollars should pay to save their houses and they should be billed. Was happy to be able to transport some animals from the Durango shelter to Loveland–a number of shelters and volunteers went beyond the call of duty and did a great job for the entire community of people who own animals.

Phyllis – thanks for being one of those people who stepped up to support other members of the community during the 416 fire, and continue to do so! You bring up some issues regarding forest policy including funding and management choices – we’ll definitely explore those in coming blogs. And certainly we are now to some extent dealing with forest management decisions made over the past century – certainly some pieces we either did not understand and probably some of which we ignored for one reason or another. Looking ahead our challenge will be to make wise decisions derived from the latest science while we also attempt to weave in the social and economic elements with the ecologic. It’s fair to say that when we ignore the ecologic component, we pay for it sooner or later, and sometimes dearly.

Thank you for this blog. We have learned a lot from the information so many parties have provided on the fire and the efforts to contain it. One thing I do not understand, however (and do not agree with), is the decision by the Forest Service to open the forest up at this time when the conditions are still ripe for a fire. As blessed as it was, last weekend’s rain did not change the severity of the conditions we still face. As a person still in pre-evacuation status, this decision seems ill-founded and insensitive. I am curious as to the SJCA take on this decision.

I appreciate your concern Louise about the decisions around the SJNForest closing and reopening. Please know that the Forest Service pulls in a tremendous amount of data and many people to make this type of decision and it is wholly made on a number of factors (I believe there are ten criteria), all of which have measurable criteria. As you know the SJNF leadership, using their own and shared data, decided to move back to a Stage 2 closure from the Stage 3 that was in effect for some days. The SJNF Fire Management Officer Richard Bustamante presented the agency’s findings and determinations to the La Plata County Commissioners at a lengthy public meeting on June 21. Other fire officials supported the Forest Service’s movement back to the Stage 2 closure. I attended the meeting (and I will perhaps go out on a bit of a limb sharing my observations), but I believe while the commissioners completely understood the Forest Services findings and decisions they were/are concerned that the overall trend looking through the end of June was was hot, dry and even windy – not cooler, more moist and calm. The perspectives, interests and constituencies of the Forest Service and county are not entirely overlapping and therefore not necessarily in total alignment. That said, it was evident to me that the level and respect for one another is at the highest level and the cooperation between all entities during the past month has been stellar. Please know from what I have observed and the conversations I have been involved with these decisions are the inverse of snap decisions – a great deal of inquiry, analysis and consideration have gone into all closure decisions at the county and federal level. Indeed we are fortunate to have federal managers and county electeds, from what all I have seen, have the full interests of our community in their minds, probably in their hearts, too.

Jimbo, good post . Something you might cover in a future post;

Most people have a highly distorted idea about prescribed fire as a fuel treatment. Many if not most people not close to wildland fire believe that a very high number of prescribed burns escape and become uncontrolled infernos. That facts are just the opposite, an incredibly low number of prescribed burns don’t go as planned. The vast majority proceed exactly as planned with no escapes and no problems. We only hear about the 1-2 % that go bad, not the 98 – 99 % that go without a hitch. So maybe a short discussion of the facts and numbers would be useful. Also, there are two kinds of prescribed fire. Prescribed natural fire, and a prescribed burn. I grant you in the new fire regime that climate has delivered upon the west, both have risks that are higher than they were a decade ago.

Thanks Clint – in a future blog we will definitely look at the role of prescribed fires and how they play into the potential reduction of risk for our community, especially for those who work/live/play in the WUI (wildlland-urban interface). Across the SJNForest there is an uptick in the use of prescribed fires for risk reduction and resource benefit. Hopefully through the overlay of GIS layers and the temporal progression map of the 416 fire we will be able to learn something about past prescribed fire areas such as the one in the Hermosa Creek watershed (mostly on the east side and in the southern-most drainages) from about ten years ago. I can see a field trip or two brewing….

Thanks so much for the update- that’s really helpful!

Thanks Wendy!

Very helpful!

Good to know – we’ll aim for “more and better!”

Nicely done and informative. Thank you.

Excellent post Jimbo! Thanks for your efforts to compile this complex information in a coherent way. As you know and Dr. Baker confirmed, there is no black and white when it comes to our forests and fires. What we do know is that the more we know pre-fire about the landscape, the more knowledge we can gain post fire. Hopefully the wildlife escaped and thankfully no one was hurt, yet. It is amazing to see the homes immediately adjacent to the fire line in the video. Also interesting to see all the beetle kill? that did not burn. Fires are going to continue. We need to look at zoning and taking personable responsibility for our homes when we choose to build in the forests. Thanks again for all the great work SJCA does!

Hi, please list all the chemicals used to fight the fire and their level of toxicity. Also, how will climate change and a warmer world change how the forest regenerates? Will traditional species return or will non-native weeds return or is it just too hot for anything’s to regenerate? Take care. Bc

Beverly, they are exhausted! Get on the Net and do your own digging! from Llois Stein, Cortez, co.