This iconic species was once found all over North America. Now, it’s time for wolves to come home to Colorado.

Wolves in Colorado

Wolves have long stirred strong emotions in this country and still do. The idea of bringing wolves back to Colorado generates passionate support as well as die-hard opposition. Yet from an ecological standpoint, wolves belong here. And the science is clear: we can manage their introduction effectively.

San Juan Citizens Alliance has spent over 20 years advocating for habitat protection in the San Juan Mountains. In 2019, we joined the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, a coalition working to put a ballot initiative on the 2020 Colorado ballot. If passed, Colorado Parks and Wildlife will be directed to reintroduce wolves to the Western Slope by the end of 2023.

The History

Extirpation

Gray wolves once thrived throughout North America, from coast to coast and from Mexico all the way to the Arctic. But when hunters drove down the large mammal populations on which they depended, wolves turned more to livestock. This, of course, sealed their fate. The remaining wolves were hunted down by humans – shot, poisoned, and trapped until the 1940’s when none remained in Colorado.

Reintroduction

In the 1960s, gray wolves earned federal protections through what eventually became the Endangered Species Act, under which recovery of the species was mandated. In 1995, after 20 years of effort, 31 gray wolves from Canada were relocated to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho. Now, efforts are underway to bring wolves back to Colorado.

Wolf Restoration in Colorado

Wolves belong in Colorado, plain and simple. Intentional, effective reintroduction will restore Colorado ecosystems and strengthen the genetic resiliency of North American populations. We’re working to help bring wolves back home.

TOP 5 REASONS TO RESTORE WOLVES TO COLORADO

Wolves perform important ecological functions

There is no question that wolves cause profound change in the behavior of their prey and improve prey population health, creating other positive effects in their environment.

Gray wolves evolved approximately 300,000 years ago, and though many large animals have since disappeared, the wolf has continued to survive and thrive (except when faced with determined human efforts to eradicate them). Wolves now specialize in hunting ungulates, including elk, deer, caribou, moose and bison.

Because wolves evolved together with their prey and ecosystems, wolves’ hunting behavior causes changes in prey behavior that are critical to a healthy, functioning ecosystem. When wolves were eradicated from Yellowstone, deer and elk populations boomed for decades, decimating willow, aspen and cottonwoods. The river banks eroded, beavers and songbirds birds struggled, and even scavengers were pressed to survive.

Now, nearly 25 years after wolves were introduced to Yellowstone, we’ve seen that ecosystem bounce back. Wolves not only keep populations of grazers in check, but also disperse them, distributing their impact. Trees and shrubs are thriving again, stabilizing the soil and riverbanks, and also providing homes for birds and food for beavers. Scavengers can find more leftover food from wolf kills and beaver dams store more water and provided habitat for numerous other species. Learn more about these impacts below:

Prey Behavior

Hunting by wolves causes changes in prey behavior, which can create environmental change. In Yellowstone National Park, changes since wolf reintroduction in 1995 include improved conditions in riparian areas and higher survival of aspens and willows. Most researchers attribute these changes to shifts in elk behavior. Elk that stay on alert to the presence of wolves are less likely to remain in riparian areas for long periods, resulting in less intensive browsing.

Can we directly attribute these effects to the presence of wolves, and will the same effects occur if wolves are restored to Colorado? Based both on the experiences in Yellowstone and ecological theory, there is a qualified “yes” for both questions. We know for certain that elk will respond behaviorally to wolf presence, and that change in behavior will almost certainly cause positive change in environmental conditions.

Prey Selection

Wolves prey on the most vulnerable individuals, quickly determining if individuals are impaired in any way and then focusing on them. In the case of elk, those are the young and older females. Impaired animals are not only easier to catch, they also are less likely to injure wolves during the hunt.

In a Yellowstone area study, the mean age of adult females killed by hunters was 6.5 years, an age where they have multiple years of reproduction ahead of them. In contrast, the mean age of adult females killed by wolves was 13.9 years, or near the end of their reproductive years. Removal of more animals in their prime reproductive years makes the population less resilient and less able to respond to factors (like a harsh winter) that reduce population size. Wolves remove weaker individuals, which results in healthier prey populations.

Vegetation

Vegetation studies suggest changes in vegetation that occurred in Yellowstone National Park after wolves were reintroduced were likely caused by changes in prey behavior and not by reductions in prey populations. The prevailing belief is that prey animals (particularly elk) are more alert and spend less time in any one location when wolves are in the vicinity.

Riparian areas, those thin bands of vegetation along streams and lakes, are one of the vegetation types showing significant positive change. Some researchers attribute those changes to the fact that elk don’t spend as much time in those areas, allowing willows and cottonwoods to survive and grow due to less browsing by elk. There are other researchers who think the explanation is more complex and that beavers are a key factor in the re-establishment of healthy riparian vegetation. What is clear is that conditions have improved for beavers, songbirds, and small mammals. The habitat is better for elk as well, because their food sources are both more abundant and more nutritious.

Scavengers

Many species, from bald eagles to bears to beetles, rely on the carcasses killed by wolves to survive. In one study, researchers observed 221 ungulate prey carcasses killed by wolves in Banff National Park and observed 20 different species on those carcasses.

Most common were ravens, coyote, black-billed magpie, pine marten, wolverine, and bald eagles; others, in descending order, were gray jay, golden eagle, long- and short-tailed weasel and least weasel, mink, lynx, cougar, grizzly bear, boreal and mountain chickadee, Clarkʼs nutcracker, masked shrew, and great grey owl. In Yellowstone, they noted twelve scavengers, of which five visit virtually every kill: coyotes, ravens, magpies, and golden and bald eagles.

More species of beetles use carcasses than all vertebrates put together. Another study found 23,365 beetles of 445 species in two field seasons at wolf-killed carcasses. No predator feeds as many other creatures as wolves do.

Colorado is the Missing Link for Genetic Resiliency

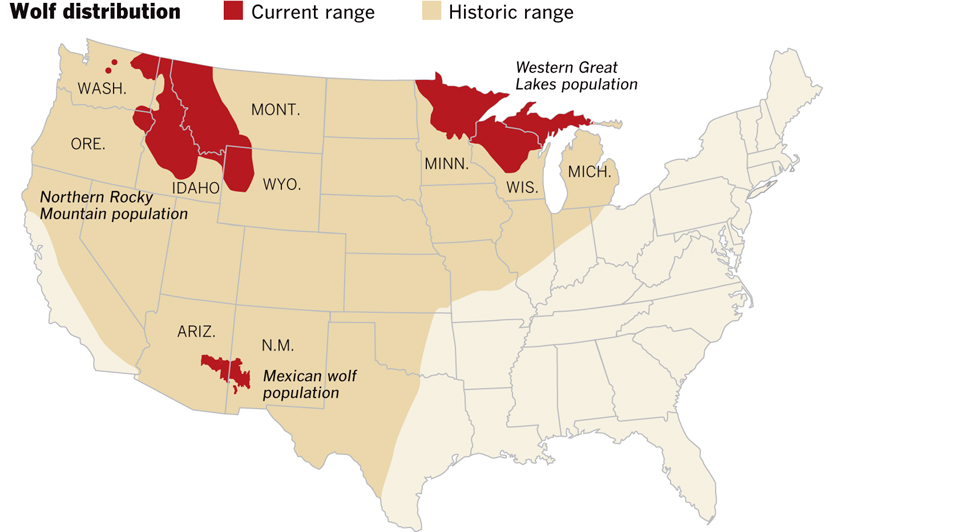

The original range of Canis lupus in North America extended from the far northern edge of Alaska to central Mexico and from the west coast to the east, except for the southeastern United States, where it was replaced by the red wolf, Canis rufus. But wolves have been driven out of their natural habitats and now only occupy about 10% of their former range.

Many juvenile wolves disperse from the area they were born and look for opportunities to join other groups of wolves or start a new pack with another dispersing wolf. This mixing of animals with different genetic makeup and resulting different physical, behavioral, and physiological characteristics maintains the ability of populations to respond to environmental change, with climate change being one of the most important factors to consider today.

The small population of Mexican gray wolves in New Mexico and Arizona would benefit from the addition of genetic diversity from wolves moving in from the north. Similarly, the ability of wolves from the northern Rockies to move south and of wolves in the southern Rockies to move north would help ensure the genetic health of both populations. Restoring wolves to Colorado is the best way to rebuild this genetic interchange.

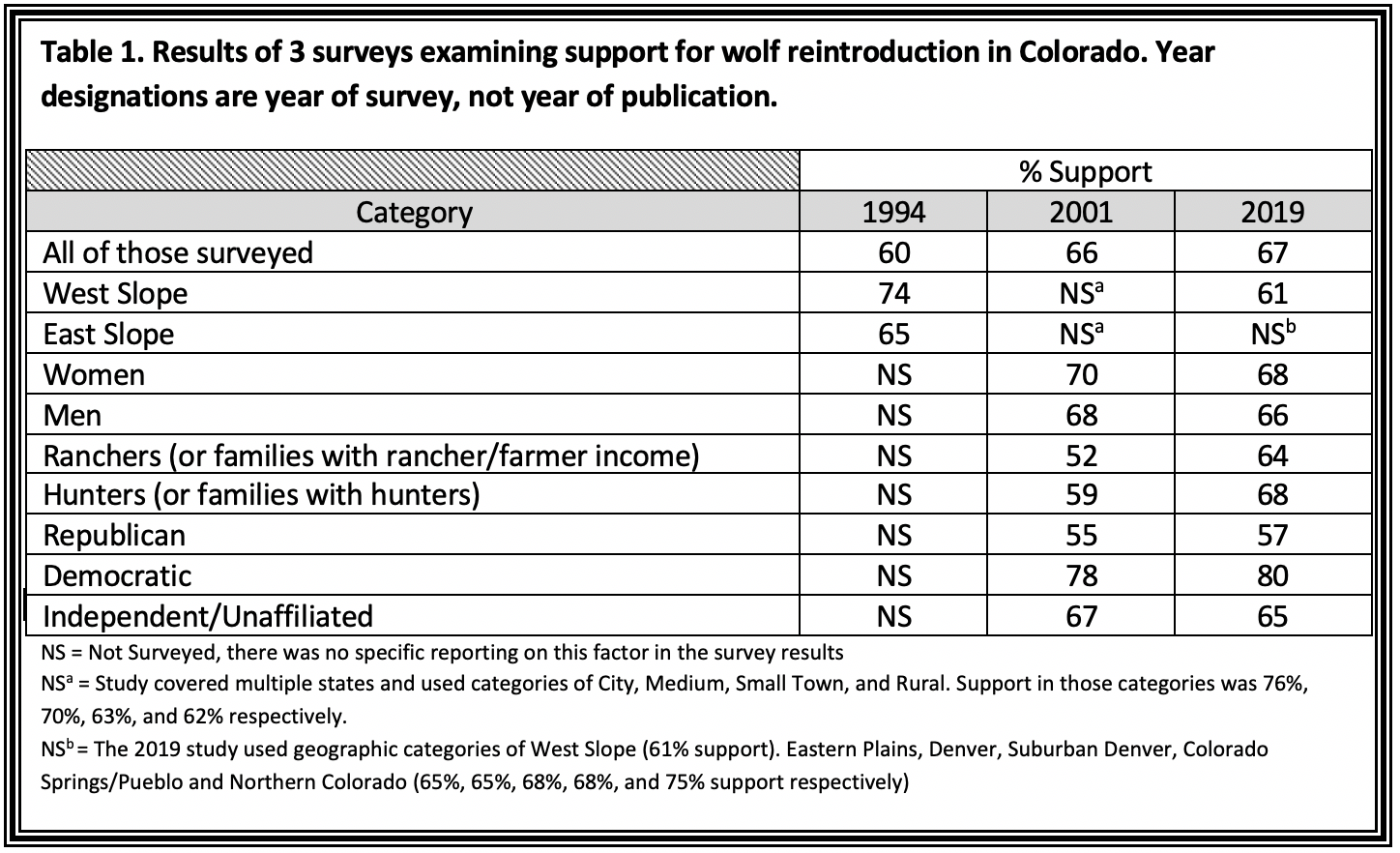

The Public Wants It

Public polling since the 1990s shows strong support for wolf restoration in Colorado. That support is broad-based, with majority support across gender, geographic location, ethnicity, and political party.

Analysis of the survey methods implies that the more people understand about the arguments for and against reintroduction, the more likely they are to support it. And the striking thing about these studies is how consistent support has been over a 25 year period, adding credibility to the results.

If and when wolves are restored to Colorado, they are likely to occupy areas with larger proportions of public lands like here on the West Slope. One commonly expressed criticism of the ballot initiative effort is that it will essentially be a case of the East Slope forcing its will on the West Slope, since Colorado’s population is concentrated along the Front Range,

It’s true that far more votes will be cast by voters along the Front Range corridor from Fort Collins to Pueblo. However, the results of the surveys indicate that the proposed ballot initiative would be supported by strong majorities on both the east and west slope. The majority of the people of Colorado–all of Colorado–would like to see wolves restored.

Intentional Reintroduction Allows Management Flexibility

Endangered Status

Right now, any wild wolves in Colorado are listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA). Even if wolves were to migrate into Colorado on their own they would still be fully protected as “endangered” under the ESA and management options would be very limited.

The ESA specifically prohibits “take” of listed endangered species. Take is defined as “…to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” In the case of wolves, strict enforcement of the ESA would prohibit actions such as chasing off a wolf that was stalking a flock of sheep.

VS.

Intentional Reintroduction

On the other hand, if wolves were intentionally reintroduced, flexibility would almost certainly be provided through an “experimental nonessential” designation, an approach used for the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone and Mexican wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. The designation relaxes ESA restrictions, treating the population as “threatened” rather than “endangered”, which allows greater management flexibility.

Past designations have allowed for actions that minimize or prevent wolf depredation on livestock that would otherwise be illegal under ESA endangered status, such as harassing or removing wolves that attack livestock and even lethal control. The classification can help with acceptance of restoration by livestock producers, local government officials, and others with concerns about wolf presence.

It’s the Right Thing to Do

Some of us view restoration as an ethical or moral obligation, because every species has an inherent right to live, and extirpating species is an ethical error. Others take a religious stance resting on the notion of protecting creation. These views end in the belief that protecting and restoring species is the “right” thing to do; that is, it’s a value judgment.

Our knowledge of the ecological role of large predators has also grown in the last century, and we’ve learned just how important wolves are to the ecosystems where they evolved.

Both for the inherent value and right to existence of wolves themselves, and for the value of intact ecosystems, restoring wolves to Colorado is the right thing to do.

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant, “What good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of eons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Aldo Leopold, father of wildlife management

Recent News (More)